Once upon a time I bought bedding plants from the nursery to grow my first ever vegetable garden. They grew well and I had a nice harvest. I thought I’d save some money on the following year’s garden, so when those plants set seed I saved seeds to plant the following spring.

The results of my first seed saving efforts were dismal. Some of the seeds molded in their paper packets over the winter. Others failed to germinate in the next spring’s garden, and those that did were spindly and disappointing.

Since then, I’ve learned that there’s more to saving seeds than just gathering, storing, and replanting. Researching the ins and outs of seed saving showed me all the things I’d done wrong, even though my seed saving idea had been a good one.

With the implementation of a few simple rules, my seed saving efforts have become both rewarding and abundant. I now save seeds to share with friends and neighbors and sell some, too.

Here are a few rules I keep in mind when I plant and select seeds for saving and perpetuating.

Consider the length of your growing season

When I plant new varieties to experiment with in my gardens, I look for seeds that produce abundantly in my short-season growing area which is only about 90 to 100 days between the last spring frost and the first killing frost of autumn. Choosing seeds that grow, mature, fruit, and produce savable seeds in my area of the country is of utmost importance.

The year I tried to grow Cherokee Purple tomatoes comes to mind. These tomatoes supposedly produce a crop in 80 to 100 days. It must be closer to 100 days because my 90-day season was over before the tomatoes produced ripe fruit. When the first killing frost arrived I hadn’t yet harvested a single ripe tomato. The vines froze with large, green tomatoes still in place. Thus, I learned three important lessons. First, I look for seeds that produce a crop in 50 or 70 days to allow for fruiting, ripening, harvesting, seed saving, and the occasional earlier-than-usual frost.

Second, I’ve learned to always start tomato seeds (peppers and eggplants, too) indoors in a sunny south-facing window or under grow lights a couple months before the last spring frost. This way my plants are already well on their way by the time it’s safe to plant them outside.

In addition, I learned that you cannot save viable seed from unripe tomatoes or green peppers. Although green peppers — both hot and sweet — are tasty in their green state, the seeds aren’t viable until the fruit has turned completely red (or to its fully mature color — some tomatoes mature to yellow or purple, too).

Saving money, saving diversity

I save seeds to save money and preserve choice for the following reasons. First, the price of commercial seeds goes up every year, and simultaneously the amounts of seeds in those packets diminish in number. Second, plants are very abundant producers of seeds. A plant produces many more than the 10 to 100 seeds found in the typical seed packet. Plant productivity of seeds ensures that the enterprising seed saver has plenty of seeds to swap, give away, and even sell.

Third, when I save my own seeds from favorite heirloom and open-pollinated varieties, I’m perpetuating seeds that have proven themselves over many generations and in my own gardens, as well. Over time, a subtle evolution takes place among plants of the same variety, and eventually they adapt to the growing conditions, soil, and climate in the parts of the country where they’re grown. Natural selection and seed saving efforts of generations of gardeners has steadily improved plants with those desirable traits that we prize so much, such as flavor, abundant harvest, disease resistance, and keeping qualities. The gradual adaptations plants make may take many generations. Therefore if we plant heirloom seeds, much of the evolving and breeding for desirable traits has already been done by our ancestors and others who have grown the plants and saved the seeds for decades and even centuries. This makes the planting of tried and true heirloom seeds a real bonus for the gardener.

A fourth reason to save seeds is that they are so easy to start in a sunny window or under a grow light, making seed saving and seed starting a budget-friendly pair of options. A growing medium, light, and water are all seeds need. And, the sprouting green plants are such a welcome sight after a long, cold winter of monochromatic colors and scenes.

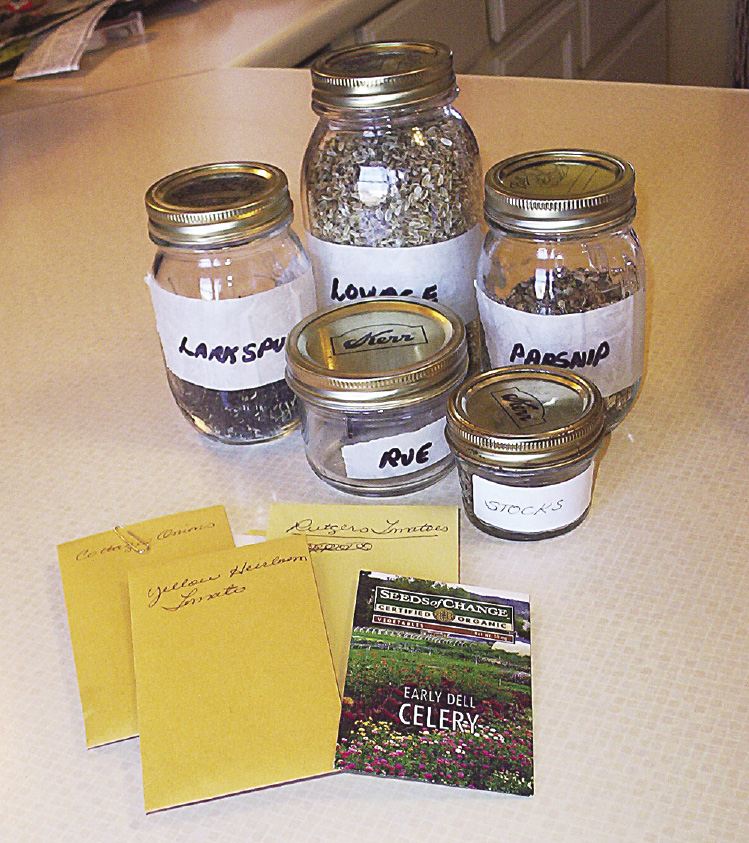

Store seeds in jars, labeled envelopes, or the envelopes they come in.

Store seeds in jars, labeled envelopes, or the envelopes they come in.Last, but not least, a very good reason to save and perpetuate seeds of your favorite open-pollinated/heirloom varieties is that corporate plant hybridizers are buying up small seed companies that sell specialty and rare seeds and replacing these with their own hybridized, patented varieties. As this occurs, our planting choices suffer and we pay more for less diversity.

To store seeds for long term, they’re gathered — usually in the autumn — cleaned, air-dried, packaged, and stored in a cool, dry spot.

An easy way to check if your stored seeds still contain enough life force to germinate is to wet a paper towel or clean cloth and squeeze out the excess moisture. Fold in half and sprinkle 10 seeds on the lower half, then fold over again so the seeds are sandwiched between. Place the towel or cloth into a plastic bag. Wait seven to 10 days before taking a peek. You’ll be able to approximate the percentage of seed viability by how many have sprouted. If all 10 sprout, you’ve got a 100% germination rate. If only five show any growth you can figure about 50% viability, and so on.

Open-pollinated, heirloom, and hybrid plants

I grow only open-pollinated and heirloom seeds. All heirlooms are open-pollinated. Open-pollinated means that when pollinated by the same variety — such as pollination occurring between Danver’s half-long carrot plants, you’ll get seeds that produce only Danver’s half-long carrots. However, if pollen from Imperator carrots pollinates your Danver’s half-longs, the resulting seeds will carry traits from both Danver’s and Imperator.

This crossing of carrots could be a good thing if you like particular characteristics of both types and want to try to breed a variety of carrot that melds those positives. On the other hand, there’s the likelihood that you may be dismayed by getting characteristics from the cross you won’t like. As an example, Imperator carrots are prettier than Danver’s, but don’t do as well in rocky soils like mine, and the Imperator crowns rot in the ground over the winter in my area, even with mulch. The short, thick, never-bitter Danver’s persist through winter and set viable seed the following spring. They’re better keepers, too, making this carrot the one I plant year after year.

Squash will not cross-pollinate with others of a different species group

Squash will not cross-pollinate with others of a different species groupPlant crossing takes time and trial and error but after many generations of selective seed saving and crossbreeding for the traits you want, you may succeed with an open-pollinated hybrid that will come true from seeds you’ve saved and perpetuated.

Saving and replanting only the seeds from those plants that have the traits you want will eventually result in seeds that reliably come true-to-form with each planting.

In this way, our ancestors created new varieties that are now our heirlooms. What you may create with cross-breeding carrots, peas, etc, will be open-pollinated hybrids of your choosing carrying only the characteristics you want to promote.

On the other hand, commercial plant breeders create popular hybrid strains each year, breeding separate secret parental/varietal lines together. Pollination is often done by hand. Achieving desired results may take many years of experimentation by plant breeders, but once success is achieved, those results are typically patented along with the breeding strategies that led to their results.

When you purchase an F1 hybrid from the nursery or home center it will not produce seeds that are like the plants you purchased. To achieve those garden center beauties, very specific plant parents are continually crossed anew each season to produce the desired hybrids. Only by crossing the pure lines again and again can that pony pack of bedding plants we buy at the nursery be created season after season — and only the original breeder has the necessary pure lines and breeding formula to do so. So F1 hybrids, although they’ll produce a tasty crop or some pretty flowers, are not of any value to the seed saver. Those seeds will inevitably produce throwbacks, as well as some drawbacks.

As an example, I bought a lovely pumpkin at the grocery store one autumn. It looked like Cinderella’s carriage pumpkin. It was ridged, kind of flat, had glossy orange flesh, and was very tasty. I assumed it was a Rouge d’Etampes variety of pumpkin, so I saved the seeds after it ripened. The next season I planted the saved seeds. I got a few small, orange pumpkins that didn’t look like the hefty parent pumpkin. I also got some very long vines that grew some zucchini-like squash that were spongy, flavorless, and looked nothing like pumpkins. And, if those throwbacks weren’t enough, I got some funny-looking squash with bottoms similar to turban squash with lots of seeds, but little edible flesh.

It was clear to me that my misidentified Rouge d’Etampes French pumpkin was not what it looked like, but was instead a hybrid of mixed parentage. The next year I ordered Rouge d’Etampes seeds to grow, harvest, save, and replant. From then on I had reliable, predictable results. A word of warning here, plants of the same family, such as many types of squash, should not be planted within a half mile or more of each other. If planting needs to be close due to space restrictions, different squash varieties will need to be isolated under netting to prevent cross-pollination by insects, or seeds of mixed parentage will result.

As an example, the squash family (Cucurbita) consists of the four species mixta, maxima, moschata, and pepo. You can plant one of each type together and they will not cross-pollinate.

However, if you plant two C. pepos together, such as zucchini and Connecticut field pumpkins, they will cross-pollinate. Although they will fruit according to type in the same year you plant them, their seeds will be of mixed heritage and will produce a hodgepodge of genetic results. They may not look or taste like zucchini or field pumpkins.

In my gardens I usually grow a crop of zucchini (C. pepo), Rouge d’Etampes (C. maxima), and Waltham butternut (C. moschata) all in close proximity, knowing there is no cross-pollination possible among these separate species. I could also grow C. mixta which are of the “Cushaw” types of squash, and those white and blue-green pumpkins seen around Halloween, but the first three species provide sufficiently for all my eating and storing needs.

Plants or seeds labeled as heirloom are those species that have been around for at least 50 years, and often much longer. They’ve been found worthy of being in our gardens by generations of growers. Because of these favorable qualities, they’ve been saved, sold and swapped, sewn into immigrants’ coat hems, toted on wagon trains, and gifted over back garden fences to beloved neighbors.

Increasingly many modern hybrids are genetically modified through gene-splicing and will not breed true. They are likely to produce seeds that, if not sterile, may have characteristics quite unlike their parents. This is a discussion beyond the scope of this article. For my part, the food I grow is open pollinated and non-GMO. Growing genetically modified or F1 hybrid seeds would completely defeat my purpose of saving seeds.

You will want to take into consideration wind and insect pollination and the proximity of neighboring gardens so that you can take steps to insure that your heirlooms remain pure. Tomatoes rarely cross-pollinate due to wind or insects, because their flowers are constructed in such a way as to make access to their pollen difficult. However, if several varieties are planted closely together you might get a cross.

Simply asking any nearby and upwind neighbors what they’re planting will let you know if your crops will need isolation by distance, wind direction, or garden mesh covering.

I like to experiment with varieties that grow best in the short growing season where I live. To that end I try one or two heirloom vegetable seeds each season, based upon catalog descriptions and results reported by my gardening neighbors. In this way, I’ve been able to find varieties that taste great, are good keepers, produce in the shorter season where I live, and have time to set autumn or springtime seeds (biennials such as carrots, parsley, and leeks set seeds usually in the spring of the following year).

Saving your seeds

Saving seeds from open-pollinated and heirloom plants is easy and fun. Save seeds only from the best, tastiest, largest veggies and fruits that are fully ripened. Most tomato fruits, for example, will be large and tasty while a few may be small and lackluster. Take seeds only from the best and most flavorful, and be sure to save seeds from many different plants in the row or block. This insures diversity and strength in future generations of plants. When I harvest carrot seeds, I take them from all the most robust plants in the rows.

When harvesting pumpkin seeds, I want to clean off most of the stringy fibers. Some types of squash have very clean seeds and I simply spread them on wax paper-lined trays to dry. With pumpkins and squash having sticky strings I’ll soak the seeds in a bowl of water for 10 minutes while I gently knead the seeds, squeezing off the strings. The seeds are then poured into a sieve and clean water run over them. Shaking the sieve gently drains away more water and settles the strings to the bottom of the sieve. Then I spread the seeds in a single layer on a wax paper-covered tray to dry. If some fibers remain, this isn’t a deterrent to either storage or planting as long as the fibers and seeds are completely dry when stored. When thoroughly dry, I put the seeds into labeled envelopes and store them in a cool, dry place over the winter. To freeze seeds I store the envelopes in a Ziploc baggy to prevent moisture damage to the seeds.

Some people save tomato seeds by putting them in a jar with water and letting the mixture ferment until it becomes a funky slurry, which rots the gel away from the seeds. For me it’s simpler to squeeze the seeds from ripe tomatoes into a cup or directly into a fine-meshed sieve, run a brisk stream of water over them, drain, then spread seeds in a single layer onto wax paper to dry. No smell, no muss, and they grow vigorously the following season. I’ve planted tomato seeds that have spent up to five years at room temperature storage, and while the germination rate declines a little each year, I’ve had success growing delicious tomatoes.

Gathering seeds from root veggies and greens (carrots, beets, parsnips, salsify, radishes, spinach, kale, collards, and lettuce) and alliums (leeks and onions) is simply a matter of allowing the blossoms to fade and the seeds to form and dry to a brown or black color before gathering them. I use an old pie tin to gather the seeds by cutting the seeds heads or knocking seeds free into the pan. Just be sure to gather the seeds on a dry day in the afternoon so no moisture remains on them, or they’ll mold in storage.

Seeds from the above crops can be stored without rinsing or cleaning in paper envelopes or glass or plastic jars. If you want really clean seeds for selling or gifting you can huff and puff lightly to blow dust and plant debris from small seeds, being careful not to blow them out of your pie tin or gathering bowl. Seeds can also be screened to remove debris.

To save beans and peas for replanting (and winter eating) allow some of the pods to dry thoroughly on the vines. Crack these open and save the hardened, dried beans or peas in jars in a cool, dark pantry or cupboard.

If I want to store seeds for a long time — several years beyond their natural germination span — I’ll put my seed envelopes in a Ziploc baggy, squeeze out extra air, close tight, and put the bag in the freezer.

Freezer storage is a way to preserve seeds for several seasons more in case of a crop failure or accidental cross-pollination. I never give away, sell, or plant all my seeds from a single season. I usually have at least three seasons of seeds saved. Then, I’ll mix and match several seasons of seeds to plant out in the spring. When I moved from Utah to Idaho I wasn’t able to plant a garden the first year. The second year, I started tomatoes from seeds I’d frozen for two years and got a luscious crop.

By inter-planting seeds saved from several seasons, I ensure more diversity in parentage and robustness when they pollinate one another. If seeds are saved from only one fruit or plant, over a period of time the plant progeny will likely weaken and become prone to disease and lack of vigor. Diversity in seed saving is the key to healthy and robust future crops.

Selecting varieties to save

Catalogs and seed packets are sources of inspiration and information. Read the descriptions on flavor, disease resistance, and length of time needed from sprouting to fruiting. Many catalogs give information on keeping qualities. I always look for varieties that have long keeping qualities in fruits such as apples and vegetables like squash, cabbage, carrots, beets, and onions. These are stored in my root cellar, pantry, or the bottom of the fridge.

Tomatoes, peppers, summer squash, greens, and most stone fruits aren’t known for keeping qualities so these are eaten fresh, dehydrated, canned, or frozen.

Each year I scan the plant catalogs for one or two plant varieties to bring diversity to my food supply. Some pass muster, others don’t. In this way, over a period of 15 years, I’ve found favorite varieties that I grow each year.

It’s fun to experiment and try growing something new to augment my diet. Trying something new each season stretches my culinary ability and tickles the palate, too. One year it might be open pollinated soybeans, another okra, purslane, or edible flowers.

When you grow open-pollinated and heirloom plants, you’ll be able to save seeds and money. You’ll garden more frugally and more fruitfully. And, you’ll definitely grow better!